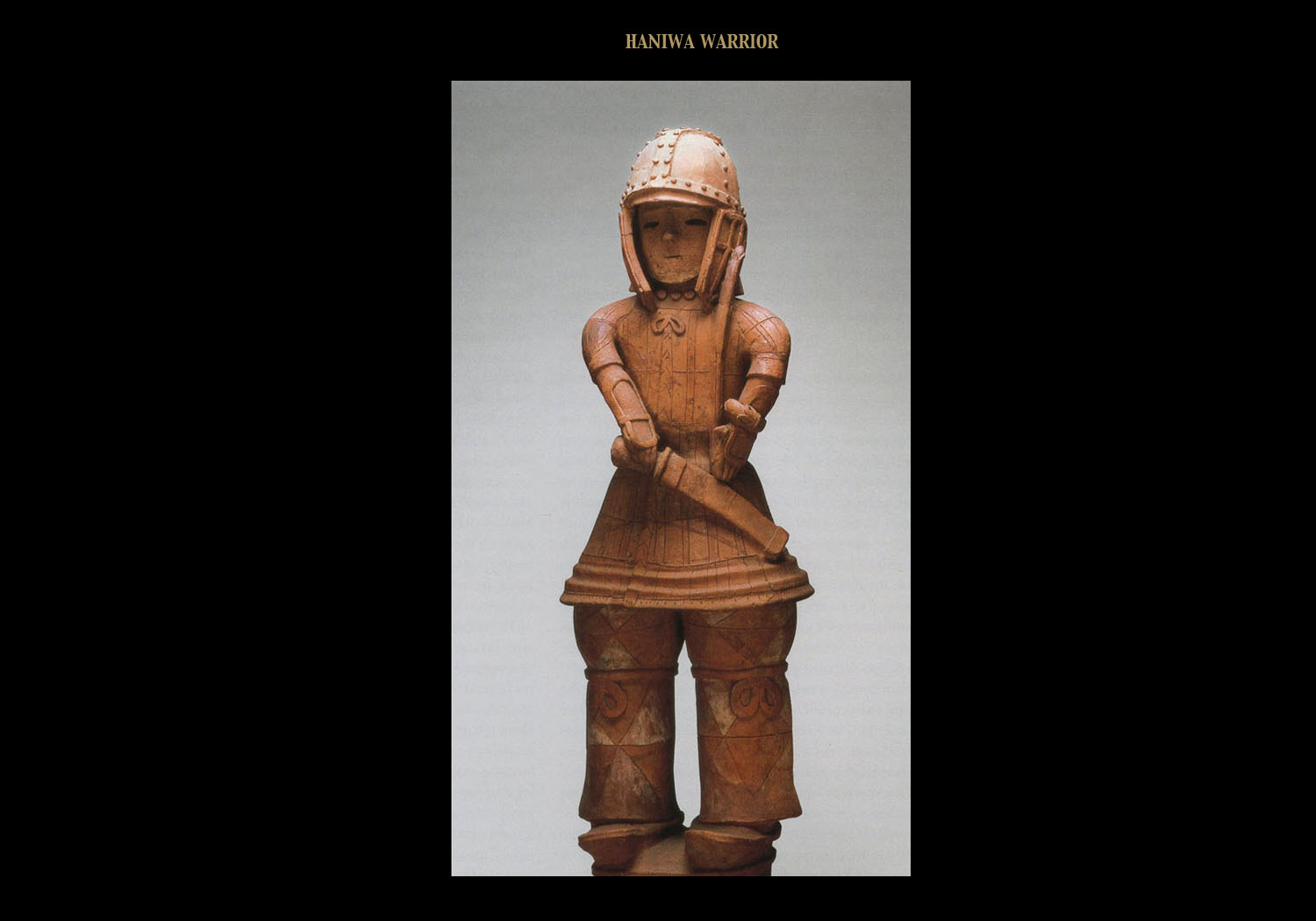

The earliest surviving examples of Japanese armor are those artifacts excavated from the great tumuli dating to the fifth century A.D. Remarkably complete armor and richly adorned arms together with clay tomb figurines, known as haniwa, depicting fully equipped warriors, provide a rather clear image of the armor from that period. These items prove that the people of Japan manufactured armor from metal. However, it should be noted that the production of armor in general, notably helmets and other protective coverings made of hides and woven vines, no doubt predates that age. Unfortunately, it is impossible to know how this ancient armor made of perishable organic materials looked.

Armor dating form the fifth century is generally classified into two types. The first is called keikô and it consists of small iron plates bound together with tanned leather thongs or cords, and is in the tradition of armor worn by mounted warriors of the Asian continent. Like other elements of the continental culture that reached Japan, this kind of armor was altered and adapted by the Japanese to suit their needs and tastes. The second type, called tankô, was a breastplate like those of the ancient Greek and Roman armor, but once again adjusted to Japanese needs and preferences.

With frequent alterations and improvements, these two types of armor continued to be used until the tenth century. By the eighth century or so, however, the battle usage of the iron plate keikô ceased and was it relegated instead to ceremonial use by the imperial court. Highly intricate, fragile, and rather heavy, keikô made up of eight hundred or so small iron plates was replaced during this time by another lighter version better suited for battle.

It was around the eighth or ninth century when Japan was finally more or less unified under a single and centralized government system. Records from this early time show that there were already certain codes designed to regulate the possession of suits of armor. In fact, privately holding such suits was prohibited and all suits of armor were declared to be the property of the government. Agents of the central government became the only legal manufacturers of armor. Standard samples of the desired design, called tameshi were sent out to each province along with the central government’s order. A certain number of copies would be made, according to the order, and these were then sent back to the government as a form of taxation payment.

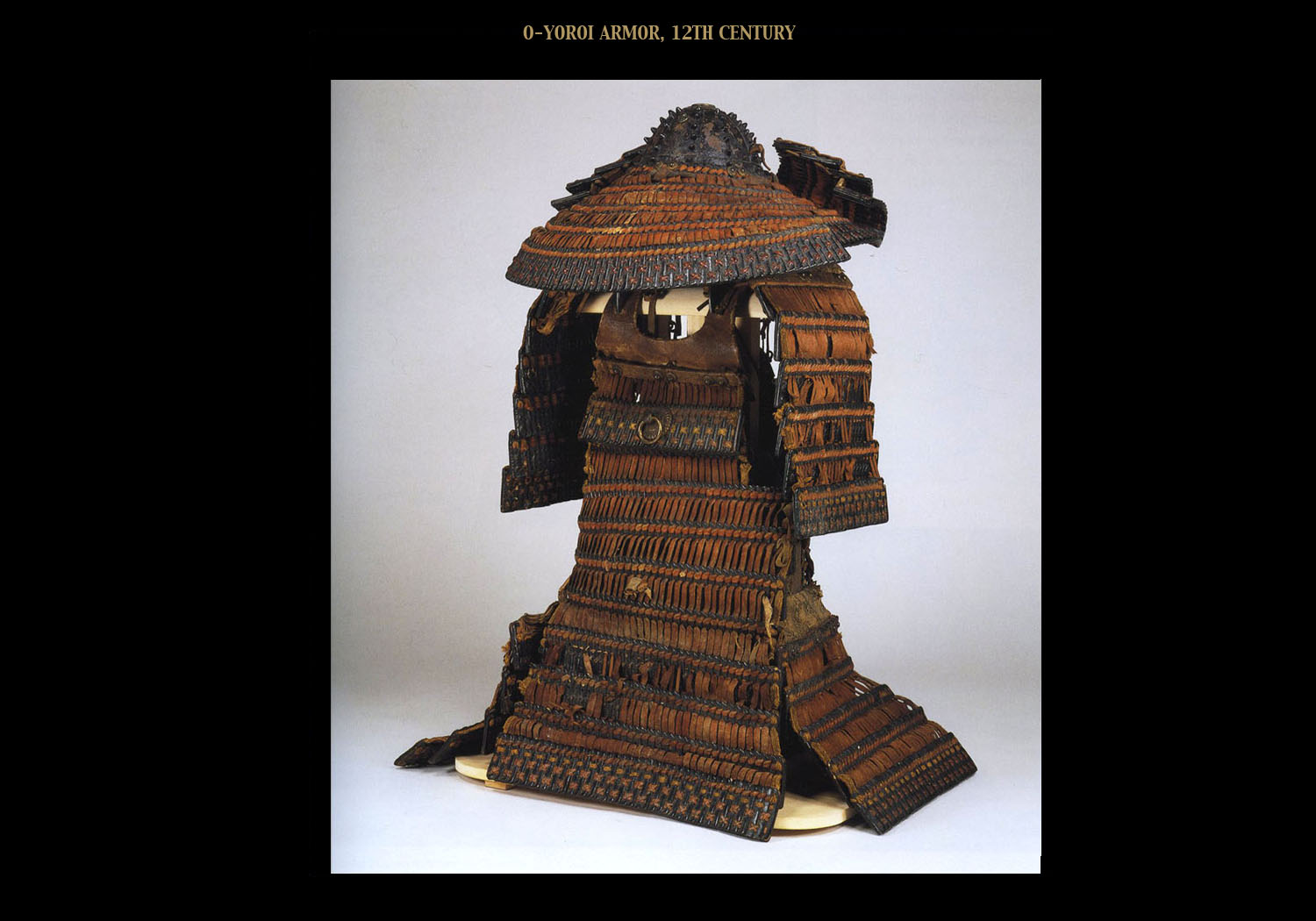

In about the tenth century, two new styles of armor emerged that replaced earlier keikô and tankô types of armor. The first was called the yoroi or O-yoroi. The yoroi was designed in response to the needs of the mounted warrior who battled with bow and arrow. This type of armor was made from rectangular leather or metal plates called sane. They were approximately 1.5 by 3.25 inches and were laced together with either leather or silk cords (odoshi). Four sections protected the torso. Three of the sections comprised the kabukidô and were joined to form the front, back, and left side protection. The right side was protected by an oblong piece called the tsuboita that was joined to the other three. The wearer’s thighs were protected by the four sections of the kusazuri that was formed of sheets of laced plates hung from a leather band affixed to the bottom of the tsuboita. The warrior’s shoulders were protected by oblong sheets called ôsode. These were formed of six or seven rows of laced together plates (sane).

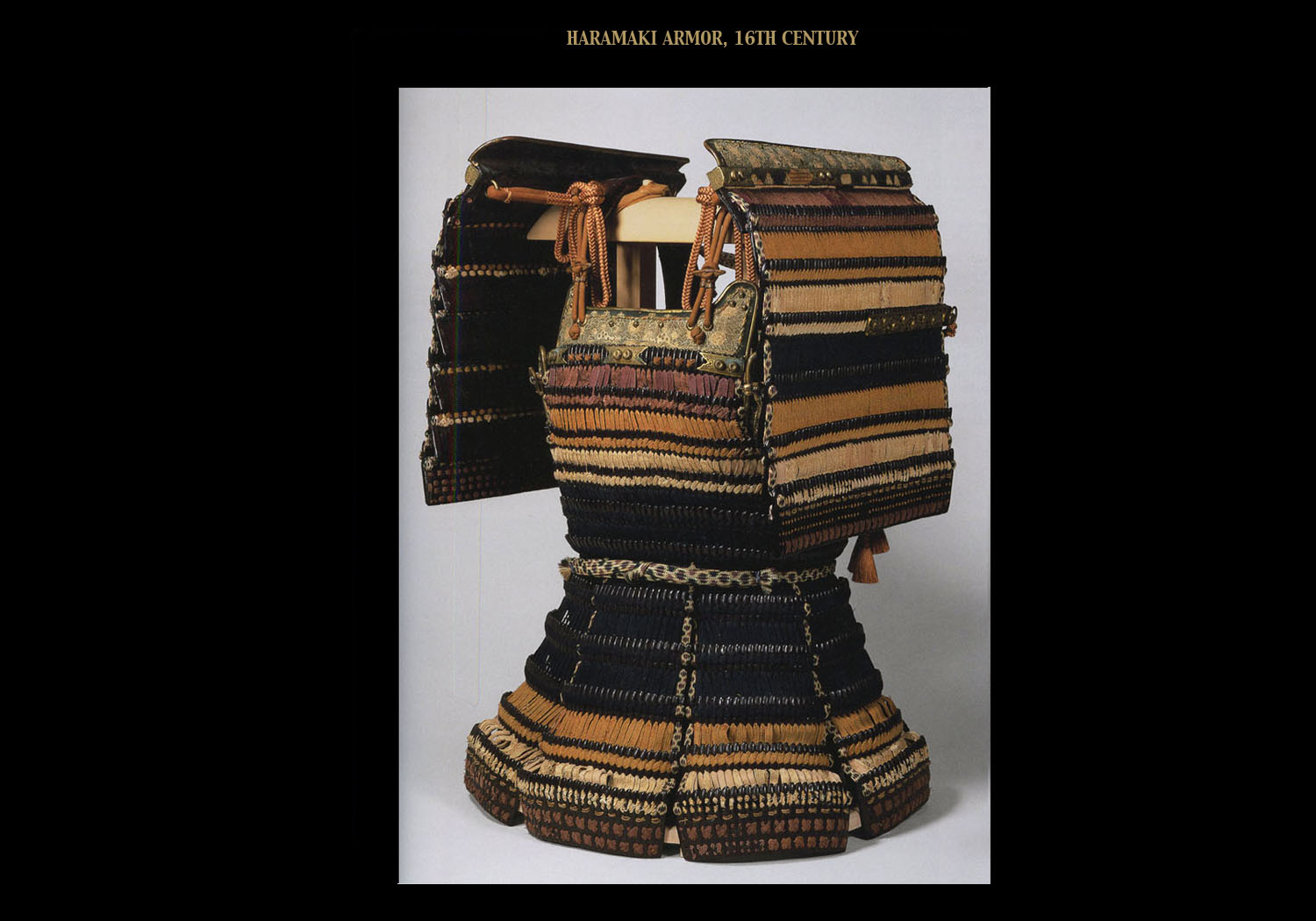

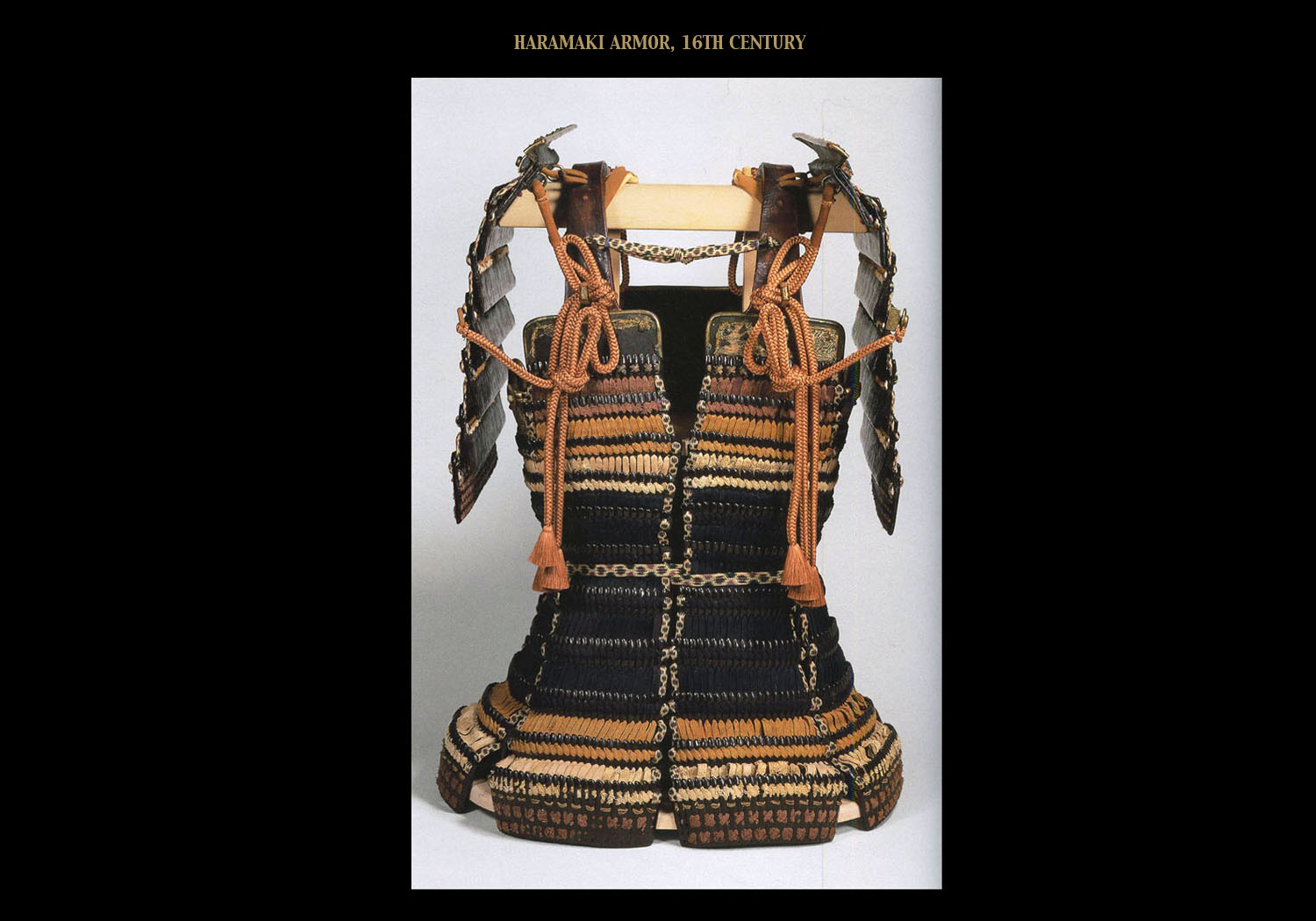

The lighter dômaru, so-called because it enclosed the trunk of the body (dô) in a round (maru) form, was the type of armor that was used by warriors requiring greater freedom of movement on the ground. In older sources, the dômaru is referred to as a haramaki, a term in use today that means “belly wrapping”. Today we differentiate between these two types of armor primarily by the way they were donned. The position of the opening (hikiawase) whereby the armor could be put on for use was different. Those with the opening down the right side are known as dômaru, and those with the opening in the back are called haramaki. The dômaru and haramaki were the first light body armor for infantry. During the Muromachi era, they came to be used with helmets and shoulder guards in the place of ô-yoroi by military commanders. The main armor parts consisting of the chest and abdomen protection only was worn by the low-class warriors.

Through the battles of the twelfth through fourteenth century, the manufacture of yoroi and dômaru were gradually improved and refined. Eventually, however, the heavier yoroi was replaced by a combination of dômaru and kabuto (helmet). By the fifteenth and sixteenth century, only high-ranking warriors with a proclivity for majestic display wore yoroi, the rest of the warriors preferred the lighter and more mobile style of armor.

The development of the Japanese kabuto (helmet) parallels the evolution of the traditional laminated body armor. The earliest helmets are of Mongolian shape; they are rounded and conical in form and built of vertical plates surmounted by an inverted semi-spherical cup.

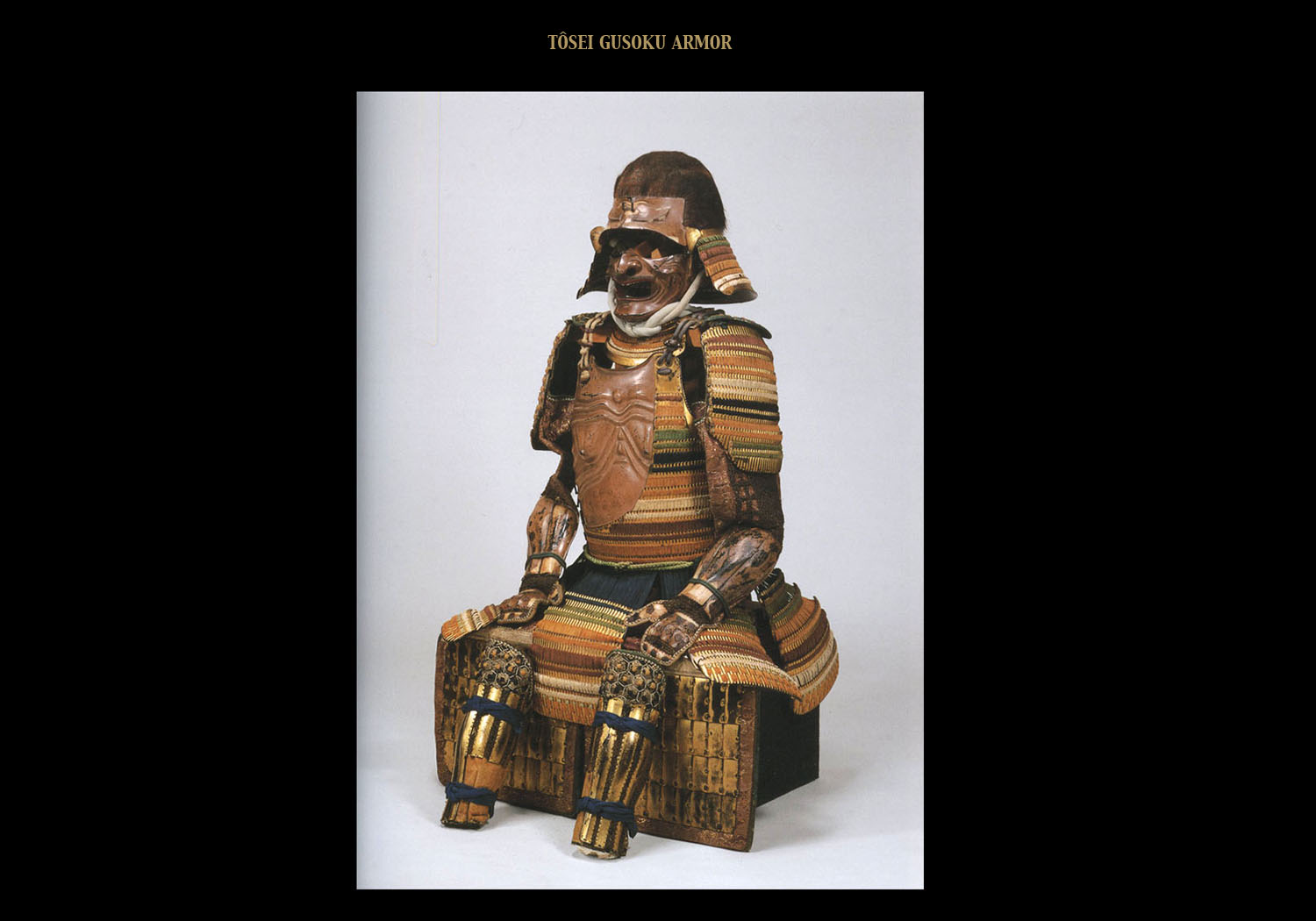

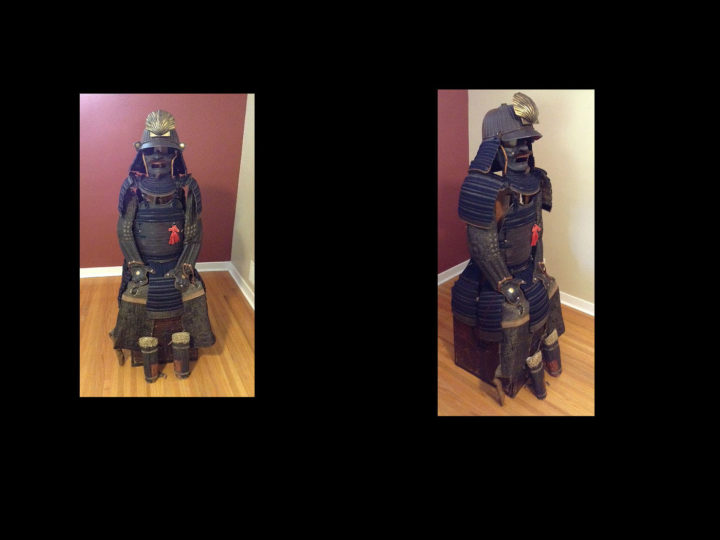

A new kind of armor and helmet appeared in the sixteenth century. It was largely inspired by European styles that were introduced by the Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch traders. During a period of more than a century of constant warfare known as the Sengoku Jidai, rapid improvements in the cuirass and helmet were demanded for greater ease of mobility, and for the enhancement of a leader’s image on the battlefields. The new armor was called tôsei-gusoku.

Helmets of the tenth and eleventh century consisted of a simple low bowl with a hole at the top for the warrior’s queue to pass through. The bowl, lined with leather and lacquered, was made up of eight to twelve plates. It was adorned with large conical rivet heads arranged in rows up the sides of the helmet bowl. A neck guard (shikoro) and lateral back turned flaps (fukigaeshi) were attached. A ring in the rear was for small flags to identify the warrior, and a heavy silk cord was used to tie the helmet under the chin. The front bore an ornament, usually an insignia or auspicious motif of some kind (maedate). Generals and high-ranking warriors, however, decorated the front of their helmets with hoe-shaped, horn-like attachments called kuwagata. Though their meaning is not clear, these kuwagata added majesty and distinction to the kabuto.

The most outstanding change in the armor of the sixteenth century, however, was the emergence of the kawari kabuto, literally “extraordinary helmets”. These unique designs were the expression of the new class of warriors, performing battles in large groups of mostly warriors on foot in open fields. In this often-confusing fighting situation, the warriors needed to distinguish their identity in some conspicuous fashion. Striking pieces of ornament thus began to appear on armor parts, specifically on the helmet. Such singularly unique, often odd, helmet forms continued to be produced throughout the Edo period until 1868.

Except for several religious rebellions that broke out in the seventeenth century, most notably the one known as the Shimabara Revolt, the military use of armor ended for all intents and purposes with the Osaka summer battle of 1615. It was at that time that the Tokugawa finalized the unification of Japan and put an end to the internal strife and warfare that plagued Japan for hundreds of years. As the nation then settled into the mainly peaceful centuries of Tokugawa rule, the aging armorers who has accumulated their great skill and knowledge during the high point of the Azuchi and Momoyama times in the late sixteenth century gradually passed away and were gone by around Meireki (1655-1657).

As the demand for armor waned, many former armor makers, especially those who made kabuto, turned to the manufacture of tsuba to eke out a living. While it is true that this had been the practice for some armors as far back as the Muromachi era, there is no doubt that the decline in the need for armor caused this practice to spread wider and wider among armor makers and, indeed, continued well into the Edo period. These tsuba are known as “katchu-shi tsuba” and they are greatly prized by collectors today as they were during the Edo period.

Bibliography:

ART AND ARMOR, Samurai Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection: Yale University Press 2014

SPECTACULAR HELMETS OF JAPAN 16th-19th CENTURY: Nissha Printing Co. Ltd., Kyoto Japan

JAPANESE ARMOR, THE GALENO COLLECTION: Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, CA