Omi no Kami Tsuguhiro (近江守継廣) was a member of the Echizen Seki (越前関) school. He was one of many swordsmiths who moved to Echizen province from Seki in Mino province around the middle of the 17th century. They were most active during the years 1658 through 1680. They worked in what we call the Shinto tokuden tradition that was fashionable at the time, as well as their original Mino tradition.

Besides Tsuguhiro (継廣), the following smiths are classified as being part of the Echizen Seki (越前関) school. Shigetaka (重高), Kanenaka (兼仲), Kanetane (兼植), Kanenori (兼則), Kanenori (兼法), Kanemasa (兼正), Kanetoshi (兼利), Kanetaka (兼高), Hirotaka (汎隆), Yoshitane (義植), and Kanenori (彭則).

Omi no Kami Tsuguhiro (近江守継廣) worked around the Kanbun era (1661). He produced swords in both Edo and Ômi. His katana generally have a pronounced mokume jihada and the hamon is normally suguba or gunome midare. He is rated as a wazamono smith (extreme sharpness). An interesting point about some of the Echizen smiths of the Kanbun period is that they did not inscribe the “Kuni name” (Echizen) on the omote, however, there were many who inscribed “Echizen Jû” on the ura. This was common with Tsuguhiro (継廣), Shigetaka (重高), Hirotaka (汎隆), and Kanenaka (兼仲).

The following are some of the more universal traits of the Echizen Seki Kei and, of course, most are also indicative of Omi no Kami Tsuguhiro (近江守継廣):

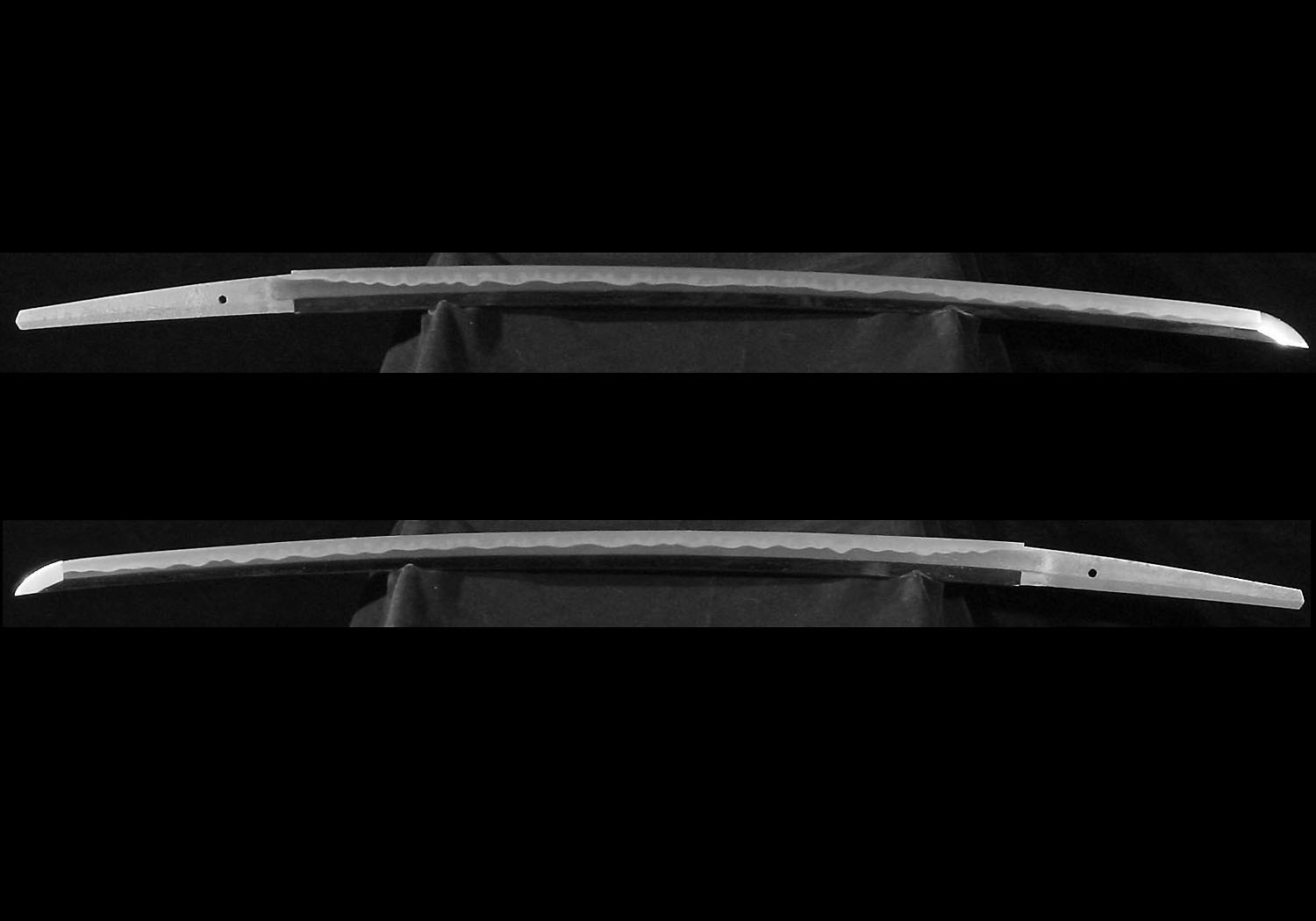

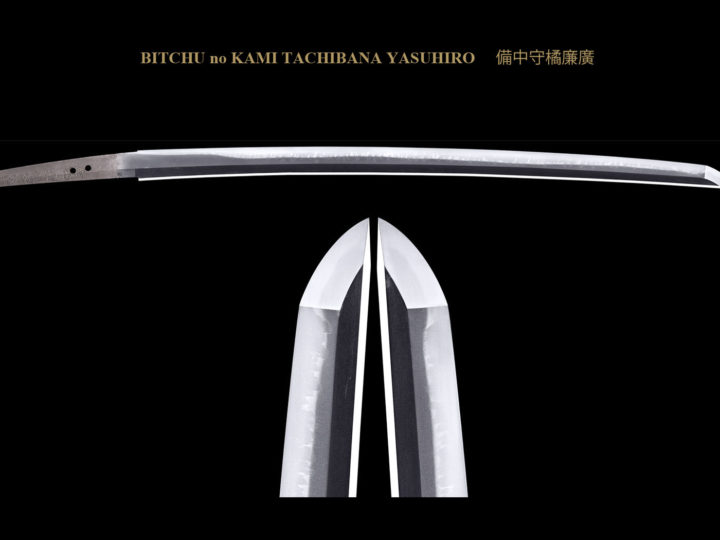

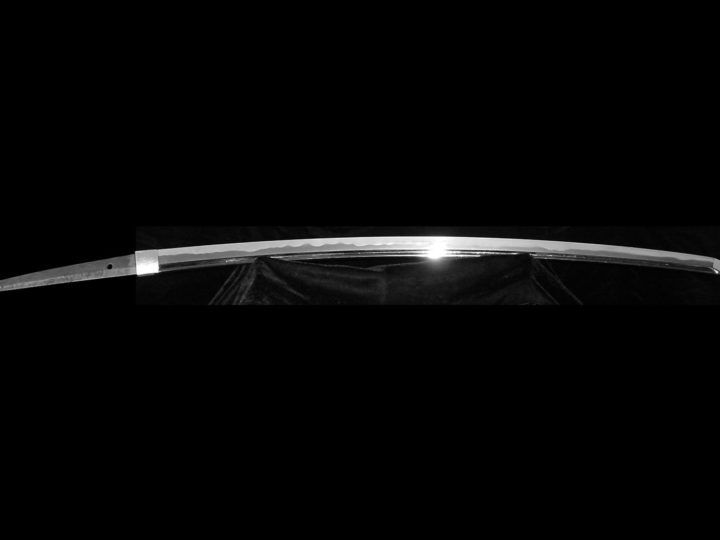

Sugata: Generally, the blades will have the special Shinto traits of this time-period. However, in many blades we do not see a very demonstrative display of the typical “Kanbun Shinto” traits that we associate with the blades of the Osaka and Edo schools of the Kanbun era. Frequently we find katakiriba zukuri, shobû zukuri, and unojkubi zukuri, especially in tantô. Overall, the sugata of the katana can be described as rustic or even somewhat awkward.

Jihada: The jigane will be hard and tight, and the jihada will tend toward mokume with some masame included. The kitae in the shinogi will be masame. Occasionally muneyaki will be found.

Hamon: The hamon is generally wide and is inclined to be nioi deki consisting of uneven nie. When it is o-midare, notare-midare, or gunome-midare, there will always be at least one area of togari-ba. If it is a wide suguba, the edge of the hamon (nioi-guchi) will be very distinct. Tsuguhiro (継廣) was known for mostly doing a hoso-suguba (wide suguba) hamon. He did, however, produce occasional gunome-midare hamon.

Bôshi: Komaru–togari (pointed) with a long kaeri (turn-back) will be the most common. Occasionally one will find muneyaki.

Horimono: Engravings will often be found on sunnobi tantô some of which will be ranma sukashi (pierced carving). Also on katana and wakizashi one will find bo-hi, kenmaki-ryu, fudo, and bonji. All carvings will be skillfully done. I could not find any direct references to it, but I strongly suspect that the famous Echizen Kinai carvers were often employed to do these carvings. We know that they worked for the Yasutsugu smiths of the Echizen Shimosaka lineage so this is a logical conclusion.

Nakago: Generally, the same as the Echizen Yasutsugu school. The nakago will be a little short, ending in kuri-jiri or kengyo. The yasuri-mei are generally kiri or katte sagari.

Mei:

ECHIZEN (no) KUNI SHIMOSAKA TSUGUHIRO 越前守下坂継廣

ÔMI (no) KAMI SHIMOSAKA TSUGUHIRO on the ura, ECHIZEN JÛ 近江守継廣……..越前住

ÔMI (no) KAMI FUJIWARA TSUGUHIRO 近江守藤原継廣