A group of swordsmiths, founded by Kuniyuki (国行) and called the “Rai school”, existed in Kyoto and thrived from the middle of the Kamakura to the Nanbokucho period. Kuniyuki (国行) never used the school name of “Rai” (来) in his mei. Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) who likewise did not use the “Rai” (来) school name followed Kuniyuki (国行). Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) was active around the Koan Era (公安)(1278-1287) and was followed by Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) who was active around the Sho’o (正応) era (1288-1292).

For as long as there have been serious studies of the history of Japanese swordsmiths, there has been a divergence of theories as to whether the smiths, Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) and Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) are two distinct smiths or just varying signatures of the same smith. Michihiro Tanobe of the NBTHK proposes the following explanation:

When we look at the extant Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) works we see that those signed with a niji-mei have a magnificent tachi-sugata with a broad mihaba and an ikubi-kissaki in combination with a chôji-based midareba that reminds somewhat of the Bizen-Ichimonji (備前一文字) school. Blades with the signature “Rai Kunitoshi“(来国俊) are narrow and elegant and show a suguha or a suguha mixed with smaller midare elements that mean they are calmer. So from the point of view just of the workmanship I would not assume at a glance that they go back to the hand of a single smith.

The most representative work of Niji-Kunitoshi(二字国俊) is probably the jûyô-bunkazai from the former possessions of the Arima family (有馬), the daimyô of the Kurume fief (久留米藩),that is nowadays preserved in the Tôkyô National Museum. It has a nagasa of 75.6 cm, a wide mihaba, no noticeable taper, a deep toriizori and ends in a compact ikubi-like chû-kissaki. In other words, this means it has a magnificent and stout shape. The hamon is a flamboyant and quite vivid midareba that consists of chôji mixed with kawazu-no-ko elements. The bôshi is also midare-komi and has a ko-maru-kaeri. The ha-nie are rather fine and unobstrusive for a Rai (来) work and, as the nie-utsuri tends partially to a midare-utsuri, the blade might look like a Fukuoka-Ichimonji (福岡一文字) at a glance. Also valuable is the ubu-nakago with its original shape. There is a bôhi with soebi on both sides but interestingly, the soebi ends on the omote side before the base and is replaced by a suken that accompanies the bôhi.

Another blade is the one and only extant tantô of Niji-Kunitoshi, the meibutsu Aizen-Kunitoshi (愛染国俊). This piece was once owned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi but came via the family of the Tokugawa-shôgun to the Maeda. The nickname, Aizen, comes from the kebori carving of the deity Aizen-Myôô (愛染明王) on the nakago. The nagasa is 2.8 cm, the mihaba is wide and the blade is altogether quite large and magnificent, that means we have here an important reference piece for the classification of tantô-sugata around the Kôan era (公安)(1278-1288). The hamon is a midare but differs from tachi examples as it is mixed with ko-notare, gunome and togari elements. The bôshi is a midare-komi with a pointed kaeri.

As we can see from the notes of Tanobe Sensei and others, the works of Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) resembled those of his father Kuniyuki (国行). Some of Niji Kunitoshi’s (二字国俊) works are even more imposing than those of his father. There are constant references to the fact that his sugata and forging characteristics will, in many ways, resemble the Bizen Ichimonji (備前一文字) school of the middle Kamakura era. While there are some zaimei blades by Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) that bear a resemblance to the general works of Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) and vice versa; there exist enough signed examples to clearly show a significant divergence of styles in the workings of both of these smiths.

Some of the basic characteristics of the Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) are as follows:

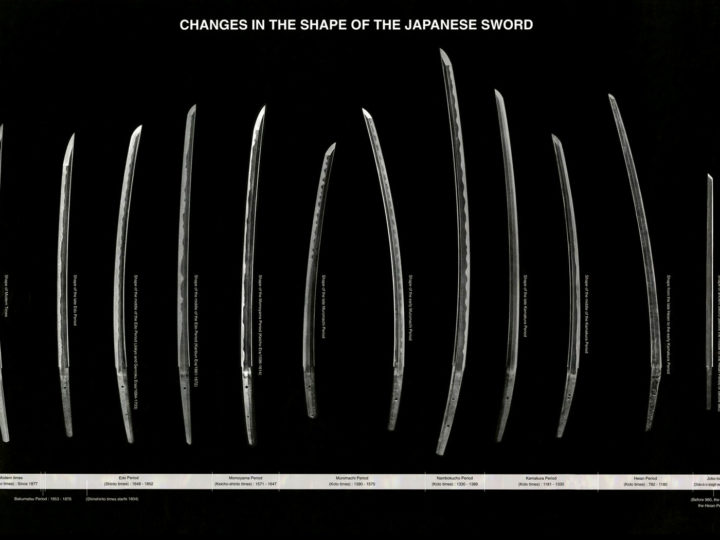

SUGATA: The tachi sugata resembles that of the works of his father, Kuniyuki (国行). There will be a wide mihaba, deep torii-sori, thick kasane, and chu-kissaki bordering on an ikubi-kissaki. There will be little or no funbari as a rule. Generally speaking, the sugata can be described as magnificent.

JIGANE: Generally itame mixed with mokume, not unlike Bizen blades of that same time period. One important difference, however, is that there will be profuse ji-nie. The ji and the ha are powerfully covered in nie, and there is both midare-ashi and nie-ashi activity. There will often be strong nie-utsuri that together with the ji-nie will not follow the course of the yakiba differentiating them Bizen blades of this same time period. This is an important difference between the schools.

HAMON: Most of his hamon will be a chu-suguha that is done in ko-midare and ko-chôji and there are some that have warabite shapes in the chôji. Warabite is Japanese for a type of fern frond. Others will be a magnificent o-chôji midare in the style of the Bizen Ichimonji school with the tops of the chôji sometimes touching the hi. In all of them there are nie-ashi and yô and sometimes other features such as niju-ba like yubashiri and muneyaki will also be seen.

BÔSHI: Generally the bôshi is midare-komi, ko-maru with a shallow return. Occasionally they will be almost ichimai in shape or yakizume will be seen.

HORIMONO: Bo-hi is the most common. One also finds soe-bi and suken and combinations thereof.

NAKAGO: While most have been shortened, the few surviving ubu nakago will be long ending in kurijiri. The yasurimei will be katte-sagari. The nakago will have niku.