With the onset of the Onin War in Kyoto (1467-1477) and the breakdown of the Ashikaga Shogunate system, the Sengoku (戦国時代) period went into full swing. The Sengoku period (戦国時代), the period of the country at war, created a time of constant warfare between rival Daimyo lords thus greatly increasing the need for weapons. A side effect of this increased demand was that the quality and effort that went into producing the outstanding Bizen (備前) swords of the Ôei (応永) era was in danger of becoming lost.

Because of the solid groundwork in sword production that was laid in the Ôei Bizen (応永備前) period and before, Bizen (備前) smiths were able to produce large numbers of powerful swords for practical use. Also, since geographically Bizen Province (備前), thanks to the Yoshii River, had a ready supply of top quality sand iron, it was relatively easy to obtain the iron necessary for manufacturing swords in quantity.

While it is popularly believed that all of the swords made during this period of constant warfare were mass produced swords of low quality, that would be a mistake. Among the blades of the Sue-koto (末古刀) period, there are a large number of what are known as chumon-uchi blades. These were special ordered blades often having inscriptions of the person ordering the blade. Additionally, these carefully crafted blades are signed differently than are the mass produced blades (kazu-uchi mono). They are signed by the smith using the kanji,Bizen no Kuni Jû(備前國住) followed by his full given name and they are usually dated. Smiths like Kiyomitsu and some of the Sukesada smiths have left many outstanding blades. One of the most respected and outstanding of these smiths was Yosazaemonjô Sukesada (与三左衛門尉佐定).

Let’s look at the typical characteristics of the works of the Shodai Yosazaemonjô Sukesada and the Nidai:

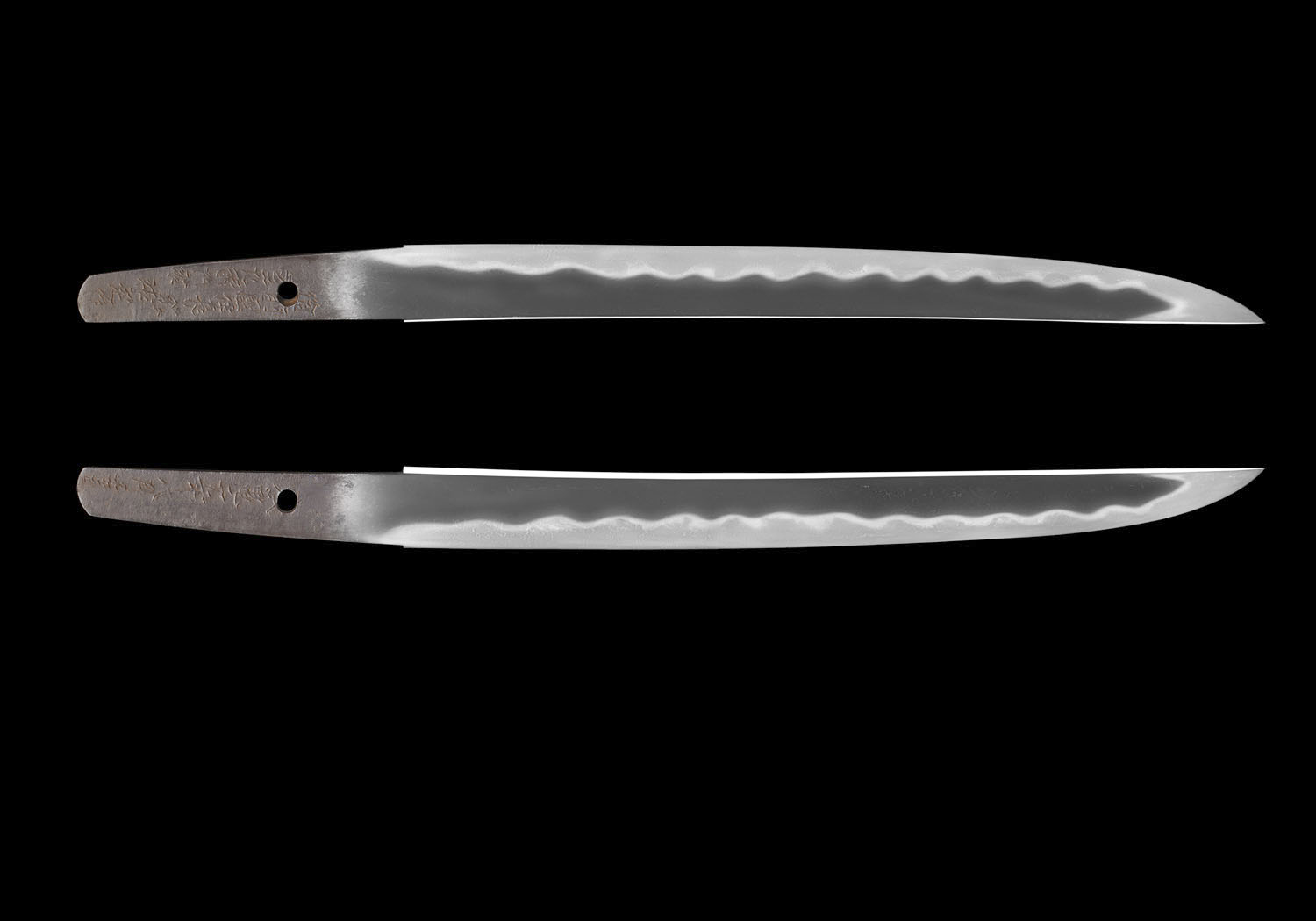

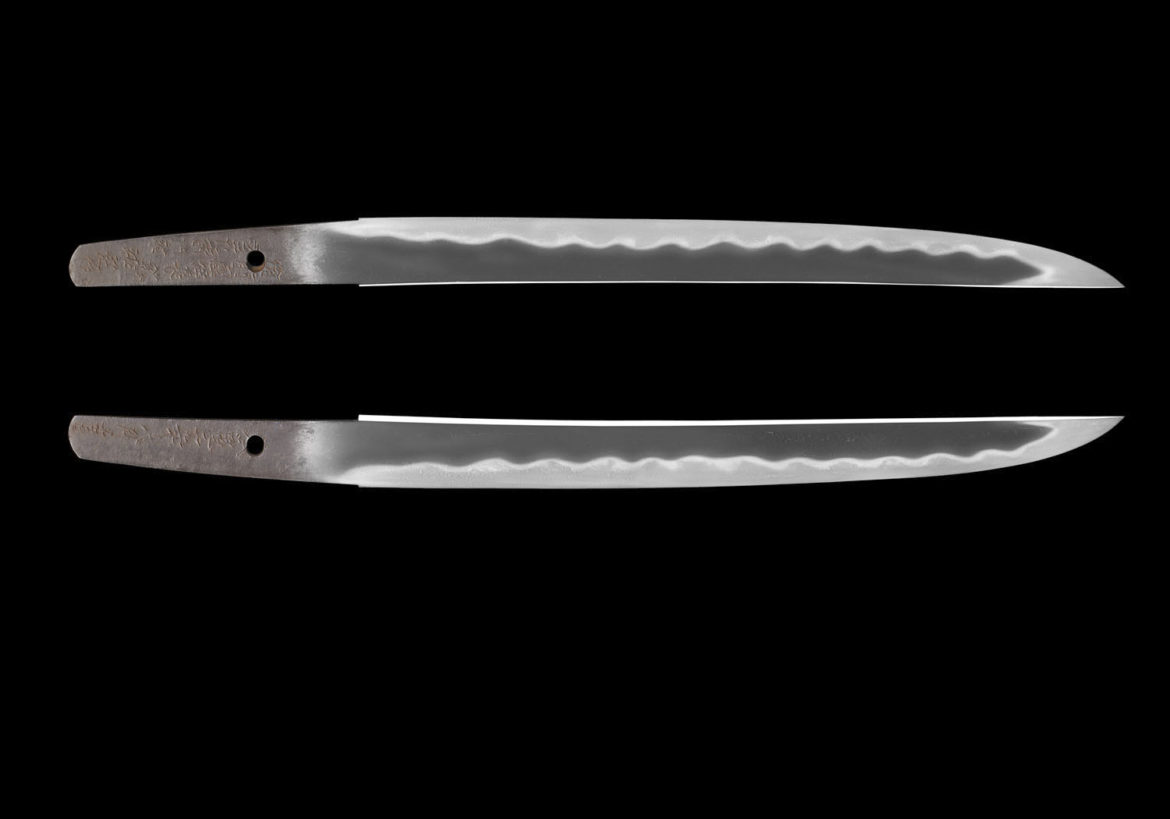

SUGATA: Uchigatana were the main swords produced in this period, followed by the hira-zukuri wakizashi, tanto of either hira-zukuri or moroha-zukuri shape, and naginata. Uchigatana during this period generally have a length of 63-66 cm, deep saki-zori, wide mihaba, thick kasane, full hiraniku, relatively small kissaki, and stout sugata. The nakago is generally short, to allow for single-handed use.

However, we find many swords by Yosazaemonjô (与三左衛門尉) that were of 2 shaku 2 sun or even 2 shaku 4 sun in length. His blades with have a stronger koshi-zori with a wide mihaba. Some of his works will have the kissaki made in the ikubi kissaki style reminding us of the Kamakura era.

Just before the start of the Shinto era, we find longer katana ranging from 72 to 75 cm. At this time the saki–zori is relatively shallow. The nakago became longer for two-hand use. Thus it seems that the rest of the smiths eventually caught up with Yosazaemonjô (与三左衛門尉).

During this period of the 1500’s sun-zumari tantô (shorter than 8.5 sun) and moroha-zukuritantô were very popular. Other than the moroha-zukuri tantô, they were hira-zukuri with a takenoko-zori with the width tapering from the machi towards the kissaki.

Sun-nobi tantô will be found at times and they are about 9 sun in length. They will be in hira-zukuri with no sori, the mihaba will be wide and there will be fukura. The kasane is made thick in proportion to the length of the blade.

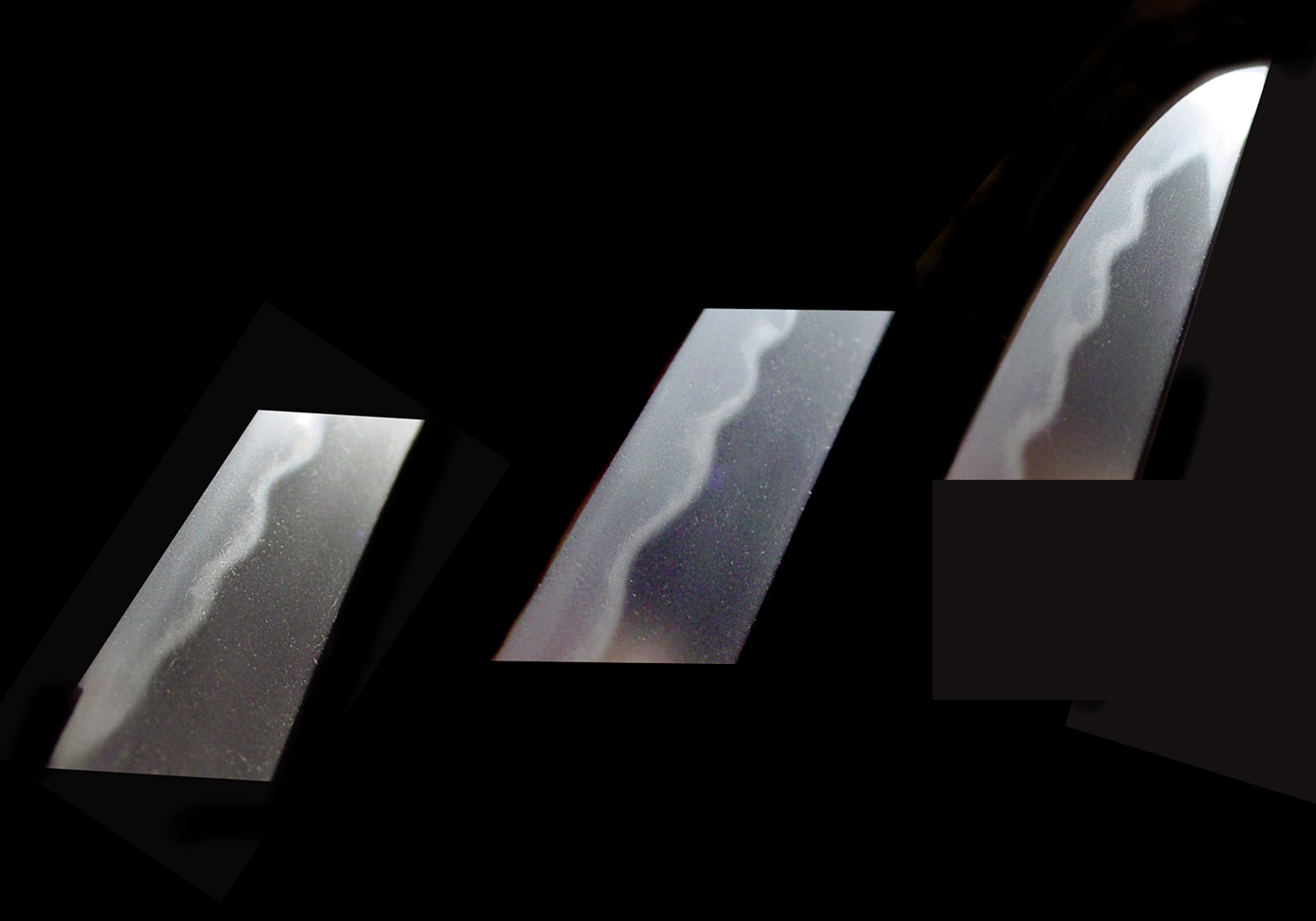

JIHADA: His kitae will generally be an itame mixed with some fine ko-mokume containing some loose as well as straight-grained areas. Blades with a fine ko-mokume hada with jinie are also found and the utsuri is neither clear nor distinct. There will be outstanding ji-nie and many chikei in the ji.

HAMON: On the whole the width of the hamon will not vary greatly throughout the length of the blade. Also, there will not be much difference in the sizes of the midare. The yakiba is nioi based as one would expect with Bizen school blades. There will be koshi biraki midare made very gently and this is one of the important traits of the Sodai Yosazaemonjô and his son, the Nidai. Occasionally hitatsura hamon will be found.

Each top of the midare has a peculiar shape which is called “kane-no-hasami” (crab’s claw). O-midare, nie-kuzure, and hitatsura are also seen. In the case of hiro-suguha, they are formed in o-notare and the edge of the hamon will be yaki-kuzure becoming ko-midare.

Regarding tantô, the width of the yakiba is made wide and in nioi. The pattern will have the koshi biraki midare in a large pattern and for the size of the blade it is made very gently. Suguha blades are seen at times and the manner in which this is made will be exactly like that of the katana or wakizashi.

With sun-nobi tantô the hamon is either hoso-suguha or the very gentle koshi biraki midare. The jitetsu will be in a ko-mokume hada with the grain of the steel standing out somewhat.

BÔSHI: When the bôshi is midare-komi, it is in proportion to and a continuation of the hamon from the lower part of the blade. The kaeri will be made deep. In tantô the kaeri can be shorter. If the tantô is a moriha-zukuri, the kaeri will continue all the way down the mune to the mune-machi. The pattern of the yakiba is exactly the same as that of the cutting side of the blade.

NAKAGO: Short and relatively less tapered nakago are found. Cho–mei (long signature) is standard in the case of custom -made works. Also included on the nakago are dates, second names (given names), and sometimes the owner’s name.