Kunihiro (国広) is considered by many to be the foremost master of all Shinto sword makers in terms of both his skill and the large number of excellent students who trained under him. In addition, he was one of the most prolific of smiths having produced swords from the fourth year of Tensho (天正) (1576) up until the year before he died in the nineteenth year of Keicho (慶長) (1614) at the age of 84.

Kunihiro (国広) was a samurai who served the Ito Daimyo who was in Obi Castle in Hyuga. His family name was Tanaka (田中) and he was commonly known as Kintaro. In the fifth year of Tensho (天正) (1577), the Ito family suffered ruin and Kunihiro (国広) began wandering the country making swords. His earliest dated sword bears the nengo of the fourth year of Tensho (天正) (1576) and he was thought to be 46 years old at that time. During this period of wandering, he included many interesting inscriptions on his nakago such as “Yamabushi-no-toki kore-o tsukuru” on a blade he made in the twelfth year of Tensho (天正) (1584). This indicates that he made this blade when he was a mountain priest. There is also a blade made in the nineteenth year of Tensho (天正) (1591) with the inscription “Zaikyo-no-toki” meaning that he made this blade while staying in Kyoto.

Kunihiro (国広) demonstrates two different kinds of workmanship. The first is called his “Tensho-uchi” or “Koyu–uchi” which indicates the style of blades made during his Tensho (天正) days of wandering. The second is called “Keicho-uchi” or “Horikawa-uchi” which indicates the blades he made after settling down in the Horikawa section of Kyoto. The “Tensho-uchi” swords show definite traits of Sue-Soshu and Sue- Seki influences. The “Keicho-uchi” or “Horikawa-uchi” swords show strong orthodox Soshu traits of such smiths as Masamune (正宗), Sadamune (貞宗), and Shizu Kaneuji (志津兼氏).

It is generally thought that Kunihiro (国広) was given the title of “Shinano-no-kami” (信濃守) around the eighteenth year of Tensho (天正) (1590). While there is some difference of opinion as to whether this title was given to him as a samurai or as a sword smith, most feel that it was for his skill as a sword smith that this title was awarded. There are also several early swords with the gassaku-mei, “Noshu Gifu-no-jyu Daido”( 濃州岐阜住大道). This indicates that he worked with the well-known Mino smith, Daido (大道), and shows the extent of the Mino influence in Kunihiro’s (国広) early works.

There are no dated examples of Kunihiro’s (国広) works during the period from Bunroku (文禄) (1592) to the fourth year of Keicho (慶長) (1599). This is possibly since Kunihiro (国広) is thought to have gone to Korea with Hideyoshi’s forces during this time.

The list of important smiths who learned from Kunihiro (国広) is long and impressive. Some of them were, Osumi no Jo Masahiro (大隅掾正弘), Izumi no Kami Kunisada (和泉守国貞), Dewa Daijô Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路), Echigo no Kami Kunitomo (越後守国儔), Yamashiro no Kami Kunikiyo (山城守国清), Kawachi no Kami Kunisuke (河内守国助), and others.

As I have stated, the workmanship of Kunihiro (国広) can be divided into two distinct styles. Therefore, when describing his sword making characteristics below, I will differentiate between the two styles where differences occur.

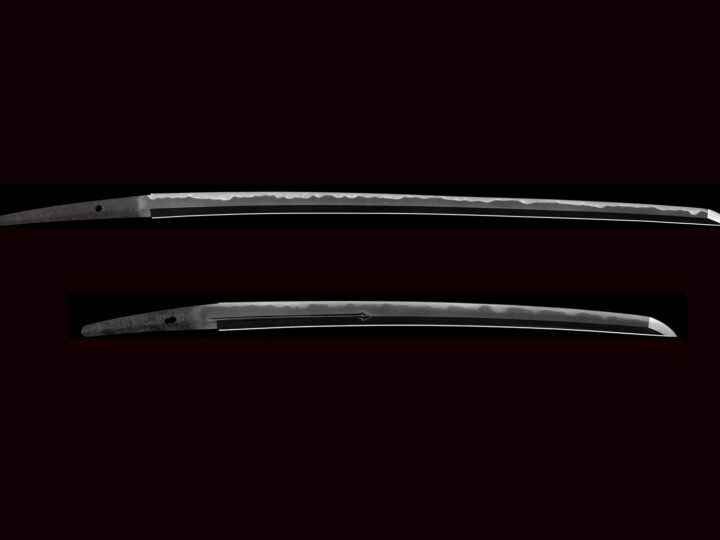

SUGATA: EARLY WORKS: Tachi and katana are usually shinogi zukuri. In his wakizashi, there are a lot of those with a wide blade. Also, there are those done in koburi (small size). Both iori mune and mitsu mune are found.

LATER WORKS: About the same as those of the early works, but occasionally a katakiriba zukuri blade can be found in the katana. Additionally, in wakizashi and tanto, hira–zukuri is most common. Iori mune is most frequent, but there are some mitsu–mune, and rarely, a maru–mune is seen.

JITETSU: EARLY WORKS: The ji–gane is of itame hada mixed with mokume hada. There is also often a trace of masame hada in the shinogi–ji. His jitetsu is almost always fairly hadadachi–gokoro showing the grain structure in a rather somewhat loose and coarse impression (zankuri–hada). This is an important kantei point for Kunihiro. However, there are some examples showing a compact texture sprinkled with fine nie forming a great amount of chikei.

LATER WORKS: Same.

HAMON: EARLY WORKS: Gunome midareba is common and display notare mixed with gunome, togariba, tobiyaki, and even hitatsura occasionally. The overall structure is nioi-deki with a rather crisp nioiguchi sprinkled with disorderly nie grains (mura-nie) and with uneven areas in the nioiguchi itself. When he made a blade in suguba, they are not simple suguba. They always display variations or irregularity such as crisp nioiguchi with ashi and hotsure, some notare, etc.

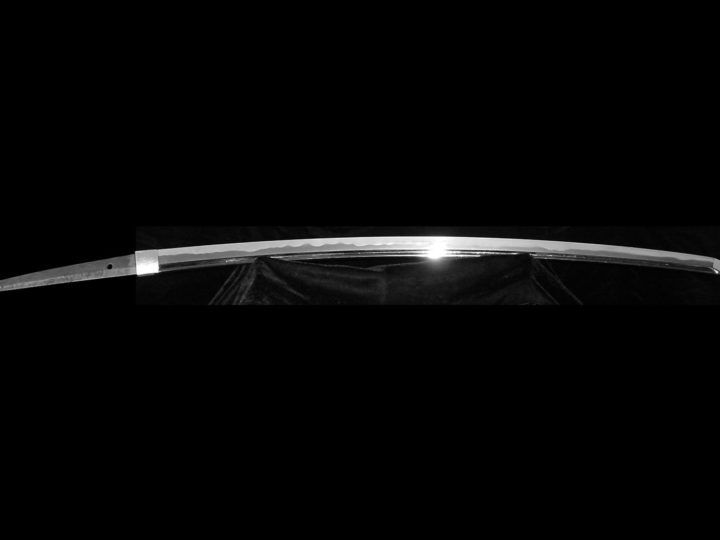

LATER WORKS: During the age of the so-called “Horikawa–uchi” period, Kunihiro went through a significant change in his workmanship style. His earlier style of Sue–koto mono (late Koto works) turned into what is known as his own “Horikawa” style. Namely he developed his basic hamon of notare containing gunome consisting of deep nioi admirably sprinkled with ko-nie and embellished with sunagashi and ashi. In some blades, there are mura–nie along the hamon. One of the characteristics common to all his works is the inconsistent width of the hamon that suddenly starts widening and increasing in exuberance in the area above the monouchi. Another important point is the wide tempering executed at the yakidashi where the hamon starts. Finally, one very important kantei point is the presence of mizukage (shadow-on-water) starting from the base near the hamachi extending upward toward the mune at an angle. Normally this is a sign of sai–ha (re-tempering), but not with Kunihiro.

BÔSHI: EARLY WORKS: Generally, midare–komi often with a hint of togari, but always with kaeri, usually longish. His bôshi are nie sprinkled some forming hakkake with a flavor of nie kuzure and some which become kaen.

LATER WORKS: Concerning swords made at that time, their bôshi are midare–komi with an almost pointed tip embellished with hakkake or rather turbulent, almost deformed midare-komi. Also, the kaeri is usually midare and there are some that are extremely yakisage (return going down the mune), becoming almost like mune–yaki.

HORIMONO: EARLY WORKS: Kunihiro’s horimono is most tasteful and impressive. Most of his blades have carvings of one kind or another. Many have bonji combined with other carvings. Often found are Hotei, Daruma, Daikoku, Bishamonten, Fudo, etc. His carvings can be every bit as impressive as his contemporary, Umetada.

LATER WORKS: No great difference can be found from that of the early period.

NAKAGO: EARLY WORKS: They are relatively stubby and the saki is not too slender. They become kurijiri with a hint of ha–agari. As for the mune, ko-niku mune are the most common and the yasurime is katte sagari or sujikai.

LATER WORKS: The most outstanding characteristic of the nakago is its length being longer than most others in general. As for the shape of the nakago, the ha side is thinned down in a shape somewhat like a boat, ending is a kurijiri shape after tapering at the tip. The yasurimei will be osujikai.

MEI: EARLY WORKS: Mostly cut in niji-mei. As already mentioned, during his “Tensho-uchi” days he often also added the location where he was residing at the time. Thus, we find mei such as “Nisshu-no-ju- Fujiwara Kunihiro Saku”. This means “made while living in Nisshu”. Most blades are dated.

LATER WORKS: While niji–mei is still the most prevalent, there are many examples with other titles such as “Yamashiro no Kuni Ichijo Horikawa Junin Shinano no Kami Horikawa” or “Rakuyo Ichijo Ju Fujiwara Kunihiro”.