When we search for the foundations of the Rai (来)school, we must first consider the Awataguchi (粟田口) school. This was the premiere Yamashiro tradition from the end of the Heian era to the latter part of the Kamakura era. The Awataguchi (粟田口) school was supposedly founded by Kuniie (国家) who moved to Kyoto (Yamashiro) from Yamato around the early 1100’s. There are no exact dates. The Awataguchi (粟田口)school flourished throughout the Kamakura era with no fewer than four swordsmiths from this school being chosen by the Emperor Gotoba around 1200 to be his sword making companions and teachers.

The Rai (来)school got its name because the smiths, in most cases, precede their signatures with the kanji “Rai” (来). One account as to the founding of the Rai (来)school says that towards the end of the Kamakura era circa 1260, Kuniyoshi (国吉) of the Awataguchi (粟田口) tradition is said to have founded the Rai (来)tradition. However, no documented works of Kuniyoshi (国吉) exist today so his son, Kuniyuki (国行), is generally said to have founded the Rai (来)school.

Another interesting theory is a slight departure in that old texts such as the Meijin Taizen say that Kuniyoshi (国吉) was an immigrant from Korea who was born in 1199 and moved to Kyoto, living there until his death in 1281. Again, there are no existing works by him so his son Kuniyuki (国行) is popularly given the credit of being the founder of the Rai (来)school.

Kuniyuki (国行) was followed by two smiths called Kunitoshi (国俊). One signed his name with the two characters Kunitoshi (国俊) and the other signed his name as Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊). For as long as there have been serious studies of the history of Japanese swordsmiths, there has been a divergence of theories as to whether the smiths, Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) and Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) are two distinct smiths or just varying signatures of the same smith. Michihiro Tanobe formerly of the NBTHK proposed the following explanation:

When we look at the extant Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) works we see that those signed with a niji-mei have a magnificent tachi-sugata with a broad mihaba and an ikubi-kissaki in combination with a chôji-based midareba that reminds somewhat of the Bizen-Ichimonji (備前一文字) school. Blades with the signature “Rai Kunitoshi“(来国俊) are narrow and elegant and show a suguha or a suguha mixed with smaller midare elements that mean they are calmer. So from the point of view just of the workmanship I would not assume at a glance that they go back to the hand of a single smith.

As we can see from the notes of Tanobe Sensei and others, the works of Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) resembled those of his father Kuniyuki (国行). Some of Niji Kunitoshi’s (二字国俊) works are even more imposing than those of his father. There are constant references to the fact that his sugata and forging characteristics will, in many ways, resemble the Bizen Ichimonji (備前一文字) school of the middle Kamakura era. While there are some zaimei blades by Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) that bear a resemblance to the general works of Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) and vice versa; there exist enough signed examples to clearly show a significant divergence of styles in the workings of both of these smiths.

Rai Kunimitsu(来国光) is conventionally understood to have been the son or student of Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊). He worked from the end of the Kamakura era into the Nanbokucho era. The earliest signed work by him has a date of Karayku 1 (1326) and the last known dated example has a nengo of Kanô 2 (1351).

Rai Kunimitsu’s (来国光) workmanship is quite diversified. He produced the typically classical suguha as well as suguha mixed with ko-gunome and ko-chôji, notare mixed with gunome, gunome-midare, and others. Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) made tachi and tantô in a variety of shapes thus making him by far the most talented among the Rai (来)smiths in terms of broadness of repertoire and applicability.

The style and characteristics of the works of Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) changed over his lifetime. In fact, the changes toward the end of his career have caused some scholars to postulate that there might have been two generations of smiths by this name. This theory will require much more study in the future as there is no strong evidence to date to support it. That aside, there can be no argument that he worked in a variety of styles and produced swords with varying characteristics over his lifetime.

SUGATA: We will break down into three periods of production:

Early stage: They were made in the style of the mid-Kamakura period of the Yamashiro tradition. They have torii-zori with a hint of saki-zori. The mihaba was a little narrow, but they have hira-niku. Kasane is thick and the kissaki is made small and short. The hamon is in nie in chu-suguha, chôji-midare with nie and nioi ashi.

Middle stage: The tachi will be the style of the late-Kamakura period with the sori made shallow. Hiraniku will be lacking and the kissaki will be made long. The hamon will be in nie in chu-suguha hotsure or chu-suguha hotsure with ko-midare and ashi. Nijuba will also be found and on occasion hiro-suguha with ko-midare. In such cases the nie will have a blotched effect in places.

Late stage: The tachi will be in the style of the Nanbokucho period with torii-zori with the sori made shallow. There will be hiraniku and the kasane will be thick and the kissaki long. The hamon will be in nie in midare or in notare-midare and the nie will have a blotched effect in places. There will be midare in the shape of hako-midare around the monouchi area.

Tantô: Many different styles of tantô were made by Rai Kunimitsu (来国光).

- Standard length in hira-zukuri with a takenoko-zori. The hamon will be made in chu-suguha with ko-nie. The hada will be a beautiful ko-mokome.

- Hira-zukuri with mu-zori. Katana hi or suken and gomabashi or bonji The hamon will be in nie and in chu-suguha or chu-suguha with midare or in o-midare in which case the nie will be very rough. There will be ashi from the nioi and profuse nie.

- These will be made in hira-zukuri with saki-zori with the length being made a little longer than the first two described above. The characteristics of the blade itself will be about the same as above.

- These will be hira-zukuri and sun-nobi in length. They will have the

sugata of tantô of the Nanbokucho period. The hamon will be made in chu-suguha and the boshi will be made in ko-maru. The steel is made exceptionally fine and will be in ko-mokume hada.

- Rarely one will fine a tantô is the shoku-zukuri or u-no-kobi-zukuri

sugata.

JITETSU: Generally the hada of Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) will be a refined and beautiful hada done in a ko-mokume or ko-itame hada. The ji-nie will be thick and contain chikei as well as powerful nie-utsuri. This will be especially true on his tantô. Occasionally what is known as “Rai hada” will be found. The term “Rai hada” refers to an area of weak jigane with a color and pattern different from the ordinary hada. This is not to be confused with openings in the blade due to excessive polishing.

HAMON: In addition to the individual hamon characteristics mentioned in the sugata section above, I would like to add the following general comment. His midare-ba tempered in his tantô consists of markedly stronger nie than on his tachi. There will also be much more profuse ji-nie on his tantô than his tachi. Just like in the works of Rai Kunitsugu (来国次), there are a great deal of Sôshû traits added to the Yamashiro tradition thus creating a powerful impression. The nie utsuri in the ji showing somewhat like yubashiri make his works powerful.

BÔSHI: It will be in proportion to the hamon and will become nie-kuzuri, hakikake or kaen with abundant nie. Longer kaeri is sometimes seen.

NAKAGO: In tachi, the nakago features hira-niku and a little sori with the tip becoming narrow. Tantô nakago are without sori unless they are of the furisode type. The tip is a shallow kurijiri. The yasurime is kiri or a gentle katte sagari.

MEI: The signature usually has three characters with the first character being “Rai” (来). Occasionally the date of forging is shown.

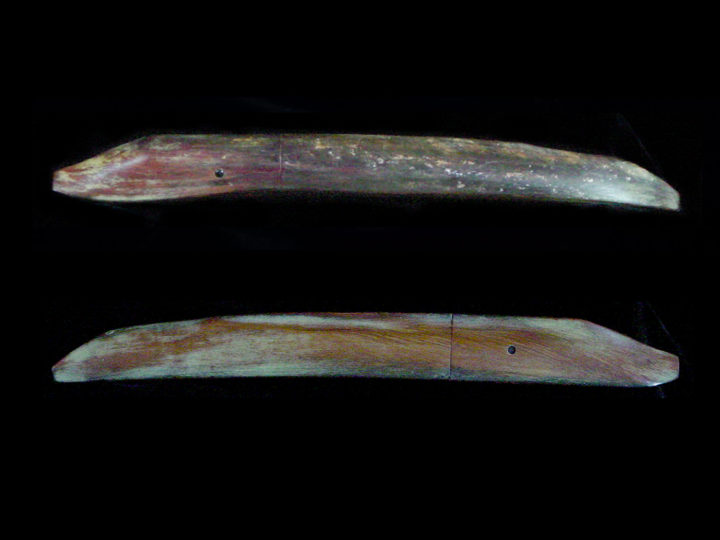

The above blade is a Jûyô Tôken tanto signed Rai Kunimitsu. The following is a translation of the Jûyô Tôken zufu for this tanto:

Designated Jûyô Tôken at the 22nd Shinsa of June 1st the 49th year of Shôwa (1974)

Tantô, Signature: Rai Kunimitsu [来国光]

Measurements: Length: 22.4 cent.; Curvature: none; Width at Base: 2.1 cent.; Nakago Length: 9.0 cent.; Nakago Curvature: 0.3.

Characteristics: The construction is hira-zukuri with an iori-mune. The blade is rather small sized. The kitae is very tight ko-itame-hada with a mixing in here and there of slightly ô-hada that is covered in ji-nie. There is prominent nie-utsuri. The hamon is suguha, and near the monouchi, the yakihaba becomes narrow. There is a slight mixing in of ko-gunome. The habuchi is covered in ko-nie, and there is kinsuji activity. The bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru. The nakago is ubu, and the tip is kurijiri. The yasurime are kiri, and there are three mekugi-ana. On the sashi-omote is a three-character signature that extends downward to the nakago-jiri.

Explanation: Rai Kunimitsu is one of the representative smiths of the Rai School during the late Kamakura period. There are tachi and tantô works that retain their signatures, and although there are both normal sized works as well as rather large sized works, this tantô has a shape that is rather small sized. This same school specialized in the tempering of a suguha with a slight mixing in of ko-gunome, and their ji-ha is superb.

This tanto is also exhibited in the new publication by Kawashima san and Tanobe san called Nihontô Shûbi (A Collection of Beautiful Japanese Swords). The description of this tanto is as follows:

This tantô, during the feudal period, was in the possession of the Arima family, who were the lords of the Kurume fief in Chikugo Province.

It has a hira-zukuri construction, and the length is seven sun and four bu, which, for Rai Kunimitsu [来国光], is a small-sized blade. Moreover, because the sword is without curvature, we can surmise that this is an early period work of this same smith. Among the works of Rai Kunitoshi [来国俊], there are also those that were signed by Kunimitsu (daimei), as well as those that were signed and made by Kunimitsu (daisaku-daimei), though with Rai Kunitoshi signatures. The nakago is ubu, and the condition is also excellent. The yasurime are clearly visible, and while we believe that this is an early period work, the characters in the signature are powerful, even now the tagane-makura (ridge left on the edge of the characters from the cut of the chisel) also remains. The jigane is very tight ko-itame-hada that is thickly covered in minute ji-nie, and there is chikei activity, making it beautiful and powerfully vivid. The hamon is tempered in suguha with slight notare, which is the hamon that was handed down from Rai Kunitoshi. The habuchi is well covered in ko-nie, and the nioiguchi is tight, bright and vivid. With Rai Kunimitsu, many of his work have a bit of a tinge of the Sôshû-den similar to Rai Kunitsugu [来国次]; however, this tantô has the feeling of following his father’s (Rai Kunitoshi’s) style of workmanship. The appearance of the shape is also close to that of Rai Kunitoshi’s elegantly refined construction.

This tantô has an accompanying koshirae, which we believe was made during the Edo period. The saya has a gold nashiji ground with a gold maki-e kurikara dragon executed on top of that. The exposed menuki are solid gold dragons, and the kozuka is shakudô with a nanako ground, and has a design of a dragon and tiger in gold iroe. The koshirae is extremely gorgeous, and it creates an impressive feeling.